Portfolios are a fairly popular tool for assessment and also

of learning. Many subject areas use this as a tool for presenting learning as

it takes place. In the recent years, most professionals (particularly in the

health and social care sector) are expected to keep a portfolio to prove their continuing

professional development and therefore fitness for registration to the

professional body and to practice the profession.

The students learn the skills of portfolio development while

undertaking professional courses. Indeed some pre university courses and

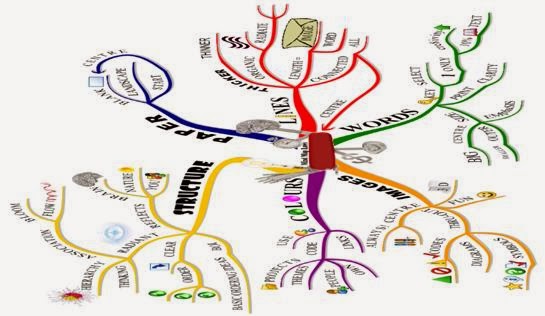

further education courses also include portfolio development. The tools I have

identified in my earlier blogs –

Learning Contract,

Concept Map and

Mind Map –

could be included in the portfolio. Indeed the Learning Contract could be used

as a framework for the development of the portfolio content.

An extract from –

Williams, M., 2003, ‘Assessment of portfolios in

professional education’, Nursing Standard 18(8): 33-37.

“In view of the need

to integrate theory and practice, assessment must relate to the monitoring of

learners' mastery of a curriculum. According to Harris et al (2001) an

educational portfolio is ‘a collection of, record or set of material or

evidence that gives a picture of an individual’s experience in an educational

or developmental situation’ (pp 278). Using portfolio as a tool can enhance the

assessment process by revealing a depth and breadth of a range of skills and

understandings on the part of the learner; support learning outcomes; reflect

change and growth over a period of time; encourage reflection; and provide for

continuity in education (Kemp and Toperoff 1998).

A portfolio can be

defined as ". . . a systematic and organized collection of evidence used

by the teacher and student to monitor growth of the student's knowledge,

skills, and attitudes in a specific subject area. It must include student

participation in selecting contents, the criteria for selection, the criteria

for judging merit, and evidence of student self-reflection . . . (therefore, it

is) a purposeful, collaborative, self-reflective collection of student work

generated during the process of instruction" (San Diego County Office of

Education 1997). Consequently as Marsh and Lasky (1984) suggest they will

provide evidence of the concepts and principles being applied in practice,

supporting the integration of theory and practice (Harris et al, 2001).

A portfolio can be

described as a systematic and organized collection of evidence to monitor

growth of the student's knowledge, skills, and attitudes in a relation to

specific learning outcomes. Student generally participates in selecting the

content, the criteria for selection and for judging merit, as well as evidence

of reflection related to learning. Therefore, it is a purposeful,

collaborative, self-reflective collection of student’s work generated during

the process of instruction and can be presented for assessment. Consequently as

Marsh and Lasky (1984) suggest it will provide evidence of the concepts and

principles being applied in practice, supporting the integration of theory and

practice (Harris et al, 2001).

Portfolios can consist

of a wide variety of materials: classroom notes, student self-reflections,

learning logs, sample journal pages or literature reviews, written summaries,

audiotapes, videotapes of group projects, reflective diary, evidence of work

carried out, witness testimonies and so forth (Valencia, 1990). However, a

portfolio is not just random collection of information or student products; but

is systematic in that information included relates to the learning outcomes.

For example, reflective diary kept by learners over a period of time can serve

as a reflection of the degree to which they are building positive professional

attitudes, knowledge and skills, one of the crucial benefits of using a

portfolio according to Harris et al (2001). Portfolios are multifaceted and

begin to reflect the complex nature of professional practice especially in

health care. Since the portfolio is developed over time, it serves as a record

of growth and progress as commented by some of the students and the supervisors

within the study. By asking learners to construct meaning from literature and

their own practice, their level of development can be assessed against set

standards (Lamme & Hysmith, 1991, Bruce & Middleton 1999).

While there are

various methods of portfolio development, majority of research and literature

on portfolios emphasize (according to Kemp & Toperoff 1998) that a

portfolio needs to clearly reflect learning outcomes identified in the

curriculum that learners are expected to study. It must focus upon

performance-based learning experiences as well as the acquisition of key

knowledge, skills, and attitudes. It should contain samples of work from the

entire time of study, rather than single points in time. It is a composite of a

variety of different assessment tools with inclusions and evaluations of that

work by the learner, peers, mentors and teachers.”

Resources

Fernsten, L. & Fernsten, J., 2005, Portfolio assessment

and reflection: enhancing learning through effective practice, Reflective

Practice, 6 (2): 303 – 309.

Lewis, K.O. & Baker, R. C., 2007, The Development of an

Electronic Educational Portfolio: An outline for Medical Education

Professionals, Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 19 (2): 139 – 147.

Grant, A. J., Vermunt, J. D., Kinnersley, P. & Houston,

H., 2007,

Exploring

students' perceptions on the use of significant event analysis, as part of a

portfolio assessment process in general practice, as a tool for learning how to

use reflection in learning, BMC Medical Education. (Online article)

McCready, T., 2007, Portfolio and the assessment of

competence in nursing: A literature review, International Journal of Nursing

Studies, 44 (1): 143 – 151.

Liu, E. Z., 2007, Developing a personal and group-based

learning portfolio system, British Journal of Educational Technology, 38 (6):

1117 – 1121.